Last Friday, while I was still in the San Francisco Bay Area, I travelled through a remote section of Marin County to the Golden Gate Recreational Area. The landscape consisted of a series of chaparral-covered high peaks which dropped majestically to the bay and ocean revealing rocky isolated coves, Cape Bonita Lighthouse, Stinson Beach and Fort Cronkhite. A windy road from Hwy 101 took me to a dramatic promontory and raptor sanctuary, Hawk Hill. I stopped at the viewpoint turn-out and was treated to one most resplendent views of the Golden Gate Bridge imaginable, a dramatically different angle of the world-famous gateway than the traditional perspective I had photographed from San Francisco the week before.

Camera in hand, I stood on a 1000-foot bluff overlooking the Bay, with the ocean at my back, looking south and east, and admired the beloved span which sometimes lay shrouded in fog and then magically revealed itself drenched with intense sunlight. The scene was like an art masterpiece, a perfectly designed architectural wonder, highlighted by one of the world's most memorable skylines in the background.

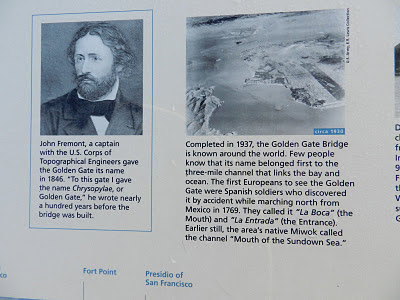

After snapping a few pictures, I noticed an information board that had been installed at the scenic overlook. It related that in 1846 John C. Fremont, a captain with the Army Corp of Topographical Engineers, had been first to map this breathtaking location and give it the title, the Golden Gate. Almost a hundred years later, in 1937, the bridge was built to accomodate the needs of the ever-expanding modern world and given the name that Fremont had recorded.

I was amused by the scarcity of words devoted to the man who had probably contributed more than any other individual to the development of the West. Identifying Fremont simply as a captain was like calling Benjamin Franklin a postmaster or Abraham Lincoln a railsplitter. Fremont had been one of the greatest American figures of the 19th century. Among his many accomplishments was that he had mapped the Oregon Trail and had written the definitive guidebook called Report and Map which was published by Congress to aid the thousands of immigrants who were traveling by wagon train, especially during the Gold Rush, to California. Also, after mapping huge chunks of the Midwest, accompanied by his guide Kit Carson, Fremont had undertaken a series of four daring expeditions across hostile Indian lands in order to explore the new frontier. His expedition of soldiers criss-crossed both the Northern and Southern Rockies in search of a suitable rail route to facilitate future development and to identify important landmarks. Fremont had also mapped the Klamath Basin, the volcanos of the Cascades and the Sierras, and the location of Lake Tahoe. He was also asked by President Polk to lead his troops in the fight to take California from Mexico and incited the murder of a number of peaceful Mexican leaders and, as second in command behind Robert Stockton, attacked and conquered Los Angeles. In addition he had fought and killed Indians in Oregon. These heroic deeds made Fremont into an almost mythical figure who became known by an adoring public as the Great Pathfinder. His life became the subject of fictional tales told in numerous penny novels which were read avidly by thousands of Easterners who yearned for a vision of adventure on the frontier.

Riding the wave of such popularity, Fremont ran for president in 1856 against James Buchanan on a platform of free land for settlers and the abolition of slavery. His campaign slogan of "Free Soil, Free Men, Fremont" resonated with many of those that embraced the idea of Manifest Destiny. He also became an avid abolitionist who opposed the extension of slavery into the new lands and had the support of the New England intellectual establishment. Although he lost, he remained popular in the drawing rooms of Washington and then was given command during the Civil War of the Army of the West and later attacked Confederates in Kentucky and Tennessee. In 1864 he ran for president again, this time as a Radical Republican against a man from his own party, Abraham Lincoln, who he believed was soft on outlawing slavery and on the treatment of the rebellious South. After the war he became Governor of the Arizona Territory, then purchased a railroad, and lived to the age of 77.

Fremont's exploits remind me how far removed my life has been from those accomplishments of true explorers. The route of my daily adventure takes me safely down major highways with the aid of GPS. Along the roadside I find cozy campgrounds with flush toilets. The only Indians I really know play baseball in Cleveland. I don't worry about disease, lack of provisions or the cold. I consider myself brave when I have hiked for the day on a well-marked trail into a wilderness which is devoid of large animals. My Golden Gate has long been charted, commercialized, and serviced by maintenance crews. When I look across the horizon at the massive blue water bisected by that iconic bridge, I know the current below me is hazardous. My path is neither gallant nor formidable nor is it my place to swim across. Yet I honor the tradition of boldness of a past time through remembrance and occasional acts of courage. From somewhere within, I can hear the call of adventure, albeit it is a muted and distant tone. The wilderness is gone. Even though a camera is hardly a six-shooter or my car a trusty mount, I explore distant lands and experience the joy of conquering the unknown. With the wind in my face, I take on the challenge.